Last Updated on January 30, 2024

This blog is contributed by Linda Ximenes. Ms. Ximenes is a member of the Tribal Council of the Tap Pilam Coahuiltecan Nation, representing the Xarame clan. She served as a member and president of the board of directors of the American Indians in Texas at the Spanish Colonial Missions for ten years. She is a Sun Dancer and pours water. In her professional life, Ms. Ximenes established Ximenes & Associates, Inc. in 1984. She has worked with non-profit, community-based organizations, public agencies and small businesses to structure and facilitate meetings and workshops for strategic planning, collaborative problem-solving, team building, and building coalitions. Her primary focus over the last 40 years has been working with community groups and organizations to give them a voice in public projects as they develop. Ximenes & Associates, Inc. is a hired consultant who has supported the Westside Creeks Restoration Oversight Committee’s meetings.

Linda Ximenes

I am a member of the Tap Pilam Coahuiltecan Nation, a tribal community made of descendants of those who built and lived in the San Antonio Missions. The Coahuiltecans historically lived from where we are in San Antonio all the way into what is now called the state of Coahuila in Mexico and across through to Del Rio. So, we are the ancestral people from this area. Ancient people knew they needed water to survive, and so there were many people congregating in this area for survival.

How did you become so connected to the land and the importance of water?

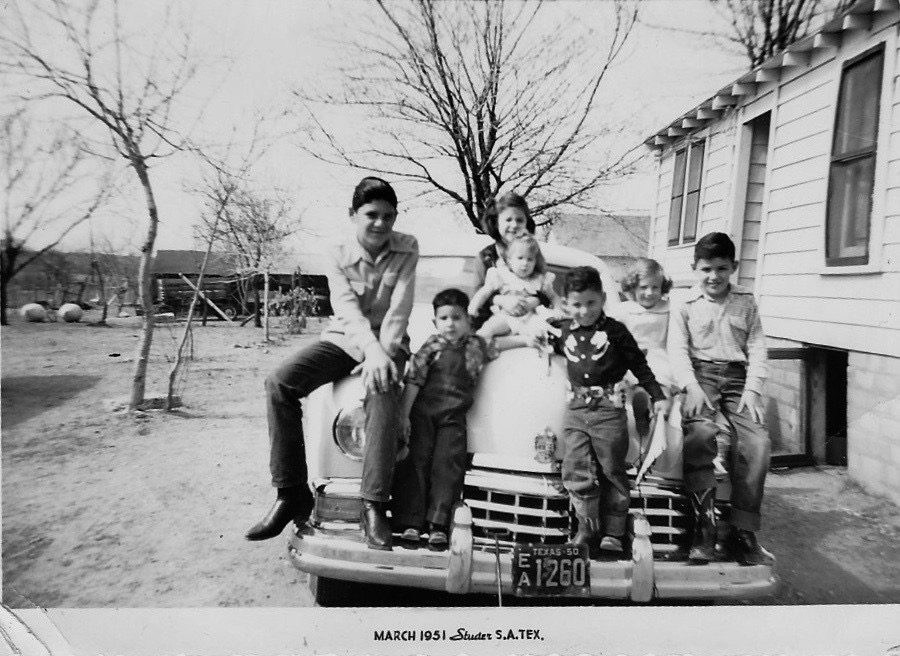

I developed a strong connection to the land from living with my grandparents. When I was growing up, my grandparents on my dad’s side had a small 5-acre farm in Floresville, a city in the southern part of the San Antonio River Basin. I would spend as much time as I could with my grandparents because I loved being there, feeding the chickens, milking the cows, and other farm chores. My cousins and I would have chinaberry fights; we’d get our slingshots and shoot the round, green berries at each other. I have a distinct memory of picking corn in their fields during the hot summers. We were sweaty and itchy because we ended up with cornsilk all over us. Being primarily a city kid, it was a memorable experience when we got to gather the corn and then go and eat it. Another distinct memory is when we harvested the watermelons. Around lunchtime, my grandfather would choose a ripe melon and put it on the table under a large Anaqua tree. He had a way of slicing the watermelon where it would leave the corazón, or heart, of the melon in the middle, and we would each get a slice. What more could you ask for in life than having a big piece of juicy watermelon when it was so hot out? During the drought of the 1950s, my grandfather would burn the spines off cacti with a “flame-thrower” so the cattle could eat the cactus pads and stay hydrated and fed. Then, when we went to my grandparents’ house to take baths, we were only allowed to fill the tub a few inches deep because water was expensive, and we didn’t want to use too much of it. So, there are all these little memories and reminders of the importance of water that I’ve picked up over the years.

The Anaqua tree at my grandparents’ home in Floresville. Photo credit: Linda Ximenes

My sisters, four of my cousins and I at my grandparents’ house. Photo credit: Linda Ximenes

Can you talk more about how you view water from an indigenous perspective?

The sacredness of water became essential to me around the same time as I was learning more about my indigenous heritage and identity. To me, water is a sacred element that you pray with and to and while you are experiencing it. You don’t take water for granted; you treat it with reverence and respect. Being close to the land matters because, even as indigenous people, we can become urbanized and lose that connection. In my community, we have a ceremony where we bless water, which we regard as a sacred element. One time, when we were performing this ceremony, there was a woman who spoke about the sacredness of the water and that we need to respect not only the water that is around us but the water that is in us. It is the recognition that more than half of our bodies are made of water. If we can respect the water that is in us, then it is a whole different way of living our lives. It is such a beautiful way to think about water in that way. We’ve also done a water ceremony a few times at the Blue Hole, the headwaters of the San Antonio River, where we bless the water and ask for a blessing in return. It is one of the ways that our community celebrates the importance of water, and often, individuals in our tribe will go to the Blue Hole on a regular basis because it is the place of our origin story as Coahuiltecans. In fact, all the land around the spring is an area of great importance for us.

In this photo, we are setting up the altar for the water blessing at the University of the Incarnate Word, where the Blue Hole is located. Photo credit: Linda Ximenes

Water can be kind, but it can also be vengeful and aggressive. One story comes to mind from a long time ago when my son was just an infant, 8 or 9 months old. My husband and I were driving back from Eagle Pass on a trip to visit his family. On the way back, we stopped in Carrizo Springs to say hello to old friends we had made while living there. It had been raining, and we were driving my parent’s car down a back road when suddenly, we hit a wall of water in the street. There was a loud “BAM” as we hit the water, and our car came to a complete stop. Before we knew it, the water had risen to the bottom of the car windows. We were in an old Cadillac with power windows, struggling to get them down. Finally, we managed to get one window down, and I handed him the baby through the open window and then crawled out. About fifteen seconds later, the car made a slow gurgling sound as the top of it slipped completely underwater and was swept away. My parents had been about to sell the car, so, needless to say, they didn’t get a very good trade-in value! As a result of these experiences and stories I have heard, I have an immense respect for water, and I also never take chances with low water crossings.

What is the best way to form relationships with our local creeks and rivers?

Understanding the importance of water is more than water conservation. It’s understanding and appreciating the role and importance of water in your life. And that, for me, is what the San Antonio River is all about. There’s something about this area and the multitude of springs that you can see bubbling up around the Blue Hole and San Pedro Springs Park when we have the right aquifer levels and get lots of rain. It’s astonishing; the water comes up through the soil everywhere and is a sight to behold.

The Blue Hole, the headwaters of the San Antonio River. Photo credit: Linda Ximenes

If you want to be more connected to the river, I suggest going to the river and just being there with it. Even though you can’t swim in the San Antonio River yet, you can kayak and walk or bike along the river. Both the Museum and Mission Reaches are absolutely beautiful, and you can really see the difference the ecosystem restoration has had on the river. Anyone who’s ever been along the river or lived along the river understands it. There’s a natural affinity and connection to bodies of water. Especially if it’s a place that is quieter, you can sit and listen to the sounds of the river and feel the magic of being there.

Photo Credit: Manuel Davila, AIT-SCM

Thank you, Linda, for sharing your story and inspiring actions for healthy local creeks and the San Antonio River. For more information about the Tap Pilam Coahuiltecan Nation, visit https://tappilam.org/