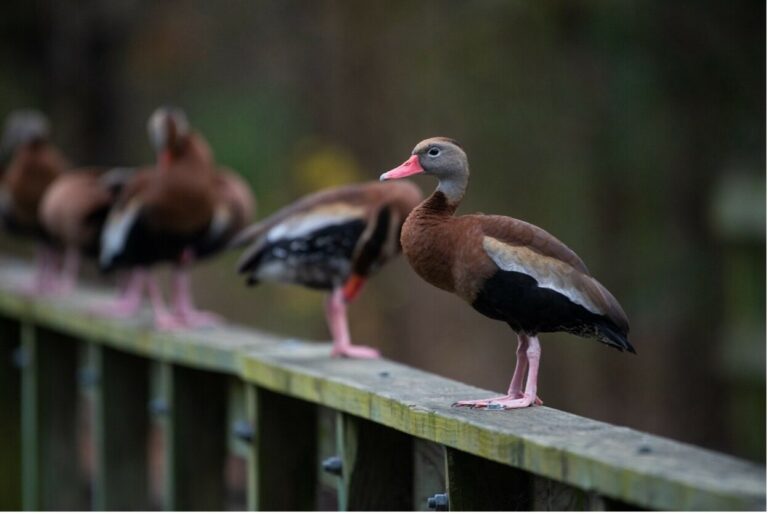

Aquatic biologists Austin Davis and Angelica Rapacz hold Largemouth bass.

After months of digging through data, the aquatic biologists at the San Antonio River Authority (River Authority) have made some exciting finds from the first three years (2019 to 2021) of the Mission Reach Intensive Nekton Survey (MRINS). The MRINS is a fish survey conducted annually within the Mission Reach, a segment of the Upper San Antonio River (USAR) that has been ecologically restored. Ecological restoration refers to repairing a stream segment by incorporating natural designs such as instream habitat and native trees on the banks. This makes the stream segment more accommodating for things like fish, bugs, and birds and positively impacts water quality. One goal of the MRINS is to determine if the ecological restoration helped various fish species return to the urban segments of the San Antonio River. Another goal is to see if a more natural channel will help promote a higher percentage of native species and push out the non-native species. Let’s dig deeper to find out!

__________________________________________________________________________

One question our biologists wanted to investigate is: How many unique fish species are in the Mission Reach?

In Figure 1 below, you will find the total number of species encountered each year of the MRINS. It can be seen from just three years of conducting this survey that many species are making their way back to a place they once called home. Higher fish diversity in our rivers generally translates to a more intact ecosystem.

Figure 1. Total number of fish species caught in each year (2019-2021) in the MRINS.

One new species our biologists identified in the MRINS is an intolerant species called the Texas Logperch. You may be thinking, why do these fish have to be so narrow-minded? However, intolerance simply means that, unlike other fish, they can handle a narrower range of habitat and water quality conditions. Because of this preference, fish like the Texas Logperch tell us quite a bit about the progression of river quality.

Texas Logperch (Percina carbonaria)

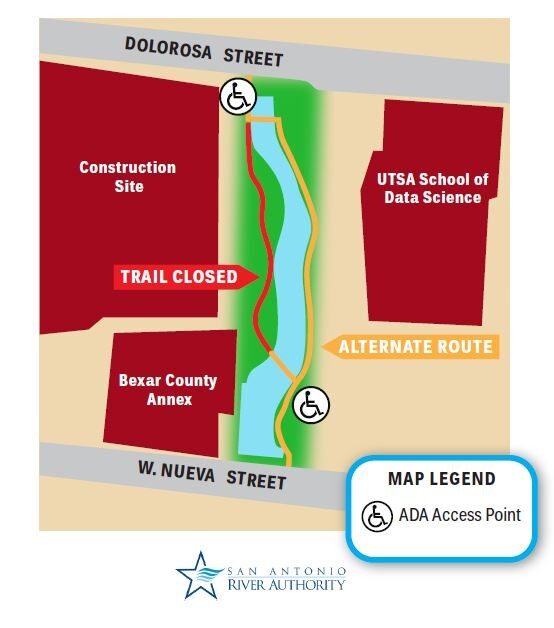

Another question our biologists wanted to investigate is: What are the most common species in the Mission Reach?

According to Figure 2, of all the fish observed over three years, 46% were Red Shiner, 9% were Western Mosquitofish, and 8% were Bluegill Sunfish. These three native fishes each serve a vital role in the ecosystem. For example, the Red Shiner serves as essential prey for larger fish like the Guadalupe Bass.

Figure 2. Most common species of fish that were observed in three years (2019-2021) of the MRINS.

A third question the team wanted to investigate was: What notable (i.e., cool and exciting) fish species were found during the survey?

Aquatic biologist Zoe Nichols holds the State Fish of Texas, the Guadalupe bass (Micropterus treculii).

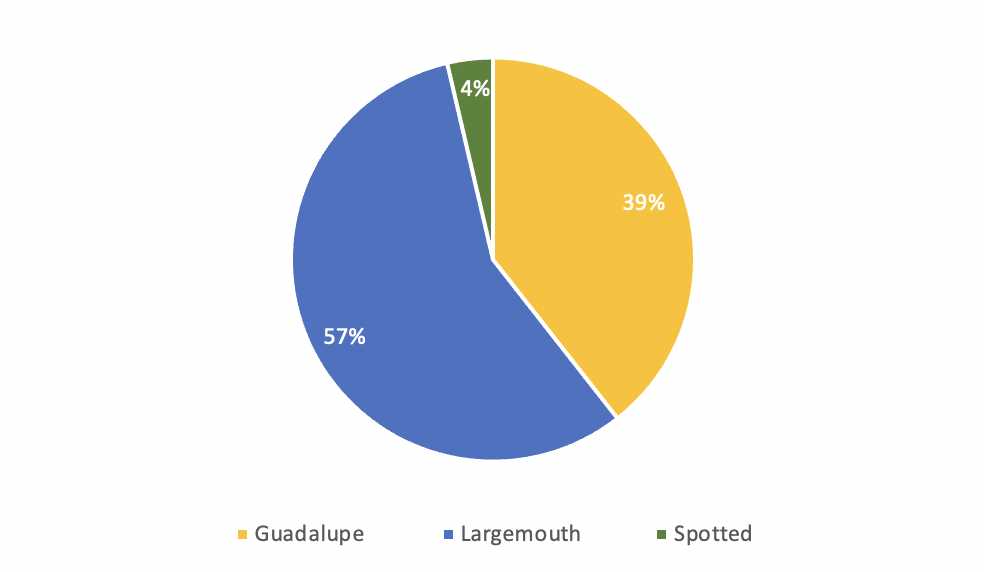

Everyone loves to catch big ol’ bass, even the aquatic biologists at the River Authority! Figure 3 shows a breakdown of the bass species that have been identified in the MRINS, with the most abundant being the Largemouth Bass. This is exciting because bass are a common recreational opportunity for anglers. The more people we can get outside enjoying this beautiful resource, the better! Heads up – Figure 3 also shows that we don’t have just one bass species in the river, so look closely to correctly identify what you catch.

Figure 3. Breakdown of bass species observed over three years (2019-2021) of the MRINS.

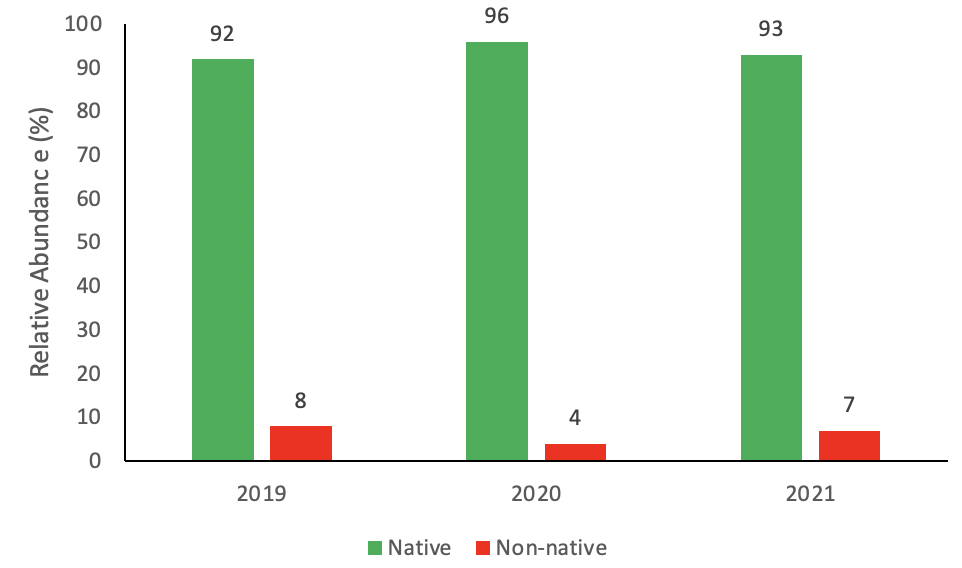

The last part of the data observed is the proportion of native and non-native fish captured. Figure 4 shows that, on average, over the three-year study, 94% of the fish our team identified were native, and 6% were non-native. There were 4 species of non-native fish identified: Blue Tilapia, Suckermouth Catfish, Redbreast Sunfish, and Common Carp. A higher proportion of non-native fish could indicate poor water quality or unhealthy stream habitats that native fish cannot live in. Overall, seeing more native fish in the river means that the restoration provided many microhabitats such as leaf litter and decomposing logs that the native fish can call home.

Figure 4. Relative abundance of native and non-native fish species over the three years (2019-2021) of MRINS.

In conclusion…

After three years of conducting the survey and analyzing the data, it appears that the ecological restoration of the Mission Reach is allowing for the revitalization of fish populations within the urban segments of the Upper San Antonio River. Additional ecosystem restoration projects are on the horizon, including the restoration of Westside Creeks. The River Authority aquatic biologists plan to conduct a similar survey to the MRINS to determine pre- and post-restoration conditions of these streams. The significant environmental justice and community benefits these projects will bring to Westside communities is an exciting prospect.

There are ways that we can keep these restored parts of the San Antonio River safe, clean, and enjoyable. Responsible fishing is essential so that the fish populations stay healthy, so pick up your fishing line and lures and don’t let litter trash your river! Don’t like fishing? There are seemingly endless hike and bike trails to enjoy and picnic tables for a family lunch in nature.

Aquatic biologists Steven Bittner and Angelica Rapacz hold the mystery fish!

Did you think we forgot about our mystery fish from the first MRINS blog? Did you identify the fish with an elongated body, heavily armored with ganoid scales, an extended jaw filled with sharp teeth, and can gulp for air? You guessed it. It’s a Longnose Gar! We know that gar species were found before the ecological restoration, but this is the first year (2021) that we have positively identified the Longnose Gar since the restoration was completed in 2013.

This is a fascinating find! Not only does it show a greater diversity of fish populations in the Mission Reach, but the Longnose Gar are also host fish for freshwater mussels. Don’t know what a freshwater mussel is?! It is the liver of the river, as many biologists say. Stay tuned to learn more about our freshwater mussel reintroduction project. You’ll be sure to pull a mussel. Literally!