Last Updated on January 30, 2024

In honor of World Wildlife Conservation Day, we’re using today’s blog to honor an iconic Texas species: the Texas horned lizard (Phrynosoma cornutum). Also known as the “horny toad” to many native Texans, this reptile plays an integral part in the food web of the San Antonio River Basin.

Toad or Lizard?

Horned lizards, horned toads, horny toads, horned frogs — with such a plethora of common names, it’s no wonder folks are confused about just what category the Texas horned lizard belongs to. Even the scientific name for the genus Phrynosoma means “toad-body,” for a horned lizard’s wide, flattened body. But don’t let their body shape and blunt snout fool you. This species is neither a frog nor a toad, but a reptile; the Texas State Reptile, in fact.

As the largest species of horned lizard, adult horned lizards measure from 3.5 to 5 inches long and have a crown of fierce-looking horns ringing their head, including two larger prominent horns at the back of their head. They also have dark brown stripes that radiate outward from their eyes and across the top of their heads. Despite their ferocious looks, horned toads are very gentle critters and lead solitary lives feeding, sunbathing, or resting in the shade.

Where do they live?

Texas horned lizards are the most widespread of all horned lizards, ranging from the south-central United States (Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, and New Mexico) to northern Mexico. Specifically, they thrive in arid landscapes such as grasslands, savannas, and deserts with sandy or loose soil and grass or shrub cover. Adapted to survive in these harsh environments, horned lizards have specialized skin that helps transport moisture from moist sand and dew across their back to their mouths. At night, horned lizards burrow underground to sleep and avoid predators. Check out this adorable video from the San Antonio Zoo of baby horned lizards burrowing. Dig, babies, dig!

Doppelganger? The Texas spiny lizard (Sceloporus olivaceus) may be confused for a Texas horned lizard due to its appearance and overlapping habitat. (Photo Credit: Peter Hernandez)

The main threat that horned lizards (and many other native threatened species) face is the increasing urbanization of rural areas and resulting habitat loss. Many homeowners choose non-native plants such as St. Augustine grass to sod their lawns and routinely mow them, eliminating the native vegetation and ground cover that horned lizards require for hibernation, nesting, and insulation purposes. Horned lizards also fall victim to moving vehicles on paved roads. Highway asphalt retains heat from the sun and makes an ideal lounging spot for the little guys, leading to many accidental killings by drivers.

What Do they eat?

Texas Christian University football fans (of which the horned “frog” is the mascot) would have you think they feast on the tears of their conference rivals, but the primary food source for Texas horned lizards is Red harvester ants (Pogonomyrmex barbatus). The lizards use their sticky tongues to quickly slurp up the ants and are immune to their venom. In fact, the formic acid produced by the ants helps keep the lizards’ blood pressure low. The habitats of harvester ants and horned lizards overlap, meaning that sometimes the best way to spot these iconic Texas lizards is to look for their prey!

Red harvester ants (Photo Credit: Peter Hernandez)

In addition to its habitat, the primary food source of horned lizards is also in peril. In the 1930s, the aggressive red imported fire ant (Solenopsis invicta) was accidentally introduced to the U.S. via cargo ships and has since spread like wildfire across our state. These invasive ants threaten native ant species due to their brutal foraging behavior, high reproductive capabilities, and lack of predators (horned lizards cannot eat them). Human efforts to control fire ants using pesticides and ant baits can be highly destructive to native ant species. It has been observed that horned lizards cannot thrive where large populations of red imported fire ants are present.

Do they really squirt blood from their eyes?

Yes! One of the most fascinating adaptations of the horned lizard is its unique defense mechanism. When hiding from predators (such as coyotes, snakes, and hawks), a horned lizard will try to use camouflage to blend into its surroundings. If that tactic fails, the following line of defense is puffing up the usually flat abdomen to appear larger than usual. If those methods aren’t working, the horned lizard can increase the blood pressure in its head, rupture the blood vessels around its eyes, and shoot an aimed stream of blood and foul-tasting chemicals up to five feet at predators.

Where Can I see Horned Lizards?

Due to the threats mentioned above, this once-abundant species is more difficult than ever to spot in the wild. A significant decline in horned lizard populations in East and Central Texas began in the 1950s, at the beginning of increasing urbanization. Today, they are primarily a fond childhood memory for older generations. In 1967, Texas horned lizards were added to a list of protected species; in 1977, they entered threatened and endangered status. Due to their calm demeanor, people frequently used to catch and keep them as pets. However, with the lizard’s perilous population decline it is now illegal to catch them, keep them, sell them, trade them, or breed them without a permit.

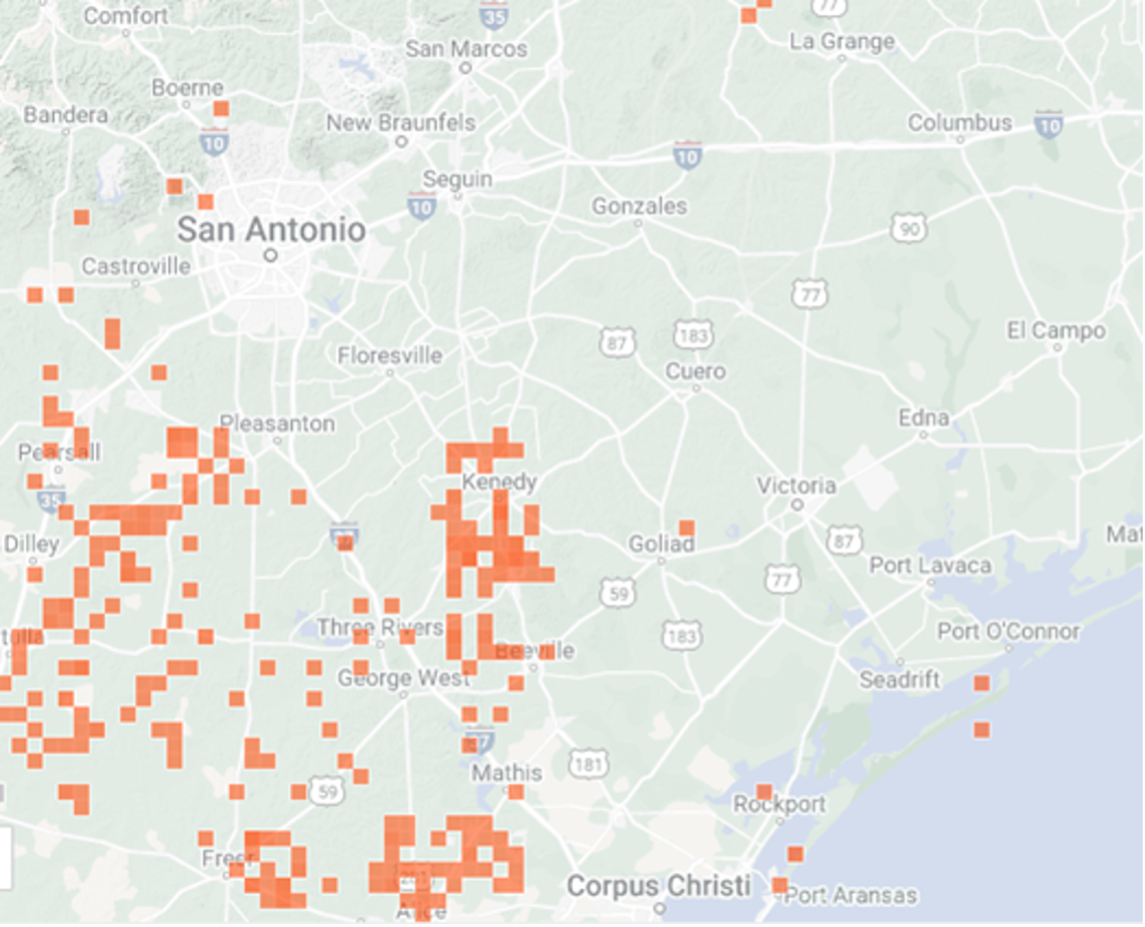

Despite their elusive nature, you can spot Texas horned lizards in the wild at places like Palo Duro Canyon and San Angelo state parks and some ecoregions of the San Antonio River Basin. Check the map below for iNaturalist for the best place to spot them!

According to observations made on the iNaturalist app (shown here), your best bet for seeing a Texas horned lizard in the River Basin is in Karnes County.

In October 2021 the River Authority completed a horned lizard habitat restoration project at the Escondido Creek Parkway in Kenedy, TX — the self-proclaimed “Horned Lizard Capital of Texas.” The one-acre project area was seeded with native plants and grasses including Little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), Sideoats grama (Bouteloua curtipendula), Texas bluebonnet (Lupinus texensi), and more. These species provide ample food supplies (seeds) for Red harvester ants, which in turn clear large areas for their nests and harvesting trails. Horned lizards look for these cleared areas, as this is where their favorite food will be, and wait for dinner to pass by. Peter Pierson, the River Authority’s Natural Resource Management Specialist, says of the project that “the seeding was very successful, and the grasses and forbs have persisted and established quite well.” Here’s hoping that our local horned lizards will decide to call it home!

The River Authority-operated Escondido Creek Parkway features many tributes including a sculpture (left) and native habitat (right).

How can I help Texas Horned Lizards?

- Keep cats indoors and supervise your pets when outdoors. Unsupervised pets can harm both horned lizards and other wildlife.

- Landscape your yard using native plants. Read about the benefits of native plants!

- Ditch the pesticides when treating fire ant mounds. Diatomaceous earth is a great non-toxic substitute!

- Join the Horned Toad Watch. Contribute valuable data and observations to this Texas Parks and Wildlife Department program that seeks to help Texas horned lizards.

- Support conservation efforts like the San Antonio Zoo’s Texas Horned Lizard Reintroduction Project.

Families at 2022’s Back to School Bash at Escondido Creek Parkway learned about the Texas horned lizard, then made their own story to contribute to the Story Wall.

For other ways to help, including turning your land into horned lizard habitat, check out this TX Horned Lizard Advocacy Guide. Together, we can help conserve this crucial species that plays a pivotal role in the ecosystems of the San Antonio River Watershed!

The River Reach is back!

River Reach is a quarterly, 12-page newsletter that is designed to inform the San Antonio River Authority’s constituents about the agency’s many projects, serve as a communication vehicle for the board of directors and foster a sense of unity and identity among the residents of Bexar, Wilson, Karnes, and Goliad counties.

If you wish to be placed on the mailing list for River Reach, please contact us or complete the form.