Last Updated on January 30, 2024

Photo Credit: Peter Joseph, River Warrior volunteer

If you are a longtime Central or South Texas resident, you have likely encountered this month’s South Texas Native in the wild! A true native, the nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) has been in the San Antonio River Basin for quite a while. Scientific reports as early as the mid-1800s found them “not uncommon” in the area.

The name armadillo means “little armored one” in Spanish and points to the protective set of plates called a “carapace” that covers much of their body, tail, and head. In fact, armadillos are the only mammals on earth to have a carapace. Their shell and the fact that they are the size of a common North American marsupial have earned them the nickname “tactical possum.” These animals are solitary and mainly nocturnal, venturing out in the early morning and evening to feast on a wide diet of invertebrates like beetles, cockroaches, wasps, fire ants, and scorpions, as well as berries and tender roots. You won’t find them eating quesa-dillos at your local restaurants, though.

Can you dig it? Nine-banded armadillos possess elongated claws on the front of their forefeet and an unusually stiff backbone, which helps them forage for food and create deep burrows. Contrary to popular belief, armadillos are not blind. However, they have poor eyesight and rely heavily on their acute sense of smell and hearing. When startled, the armadillos often leap several feet straight into the air! Unfortunately, this has led to their demise on many a Texas roadway and the acquisition of another nickname: “Texas speed bump.”

Fun Fact: Despite their name, there can be between 7-11 bands on the armor of an armadillo. Can you count the bands on this one pictured above? Photo Credit: Peter Joseph

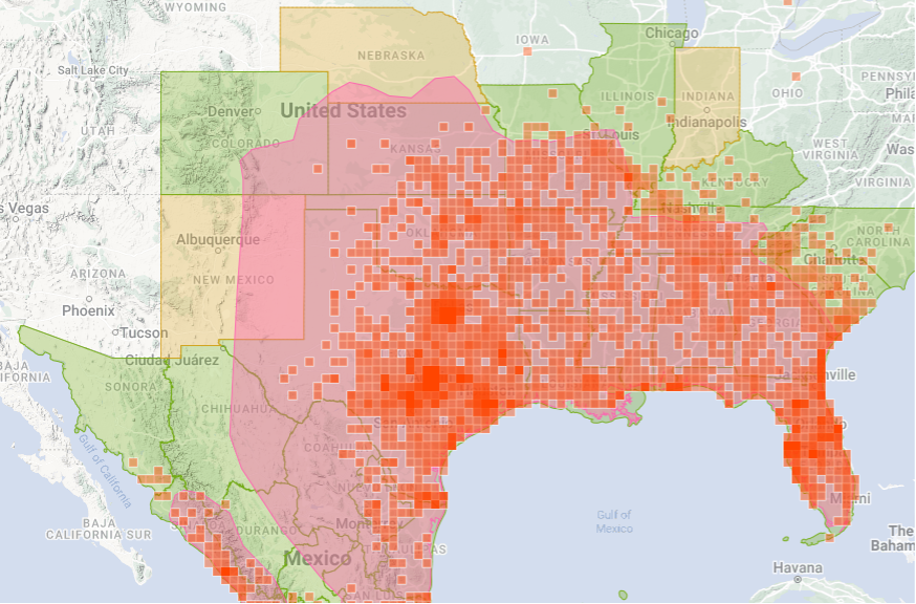

Of the 21 living species, the nine-banded armadillo is the only species found in North America and has grown into a true Texas icon. From the popularity of the 1970s Austin music venue, the Armadillo World Headquarters, to widespread armadillo racing events held on Texas Independence Day, these endearing mammals have won a place in the heart of Texans. In 1995, hundreds of elementary school students across Texas voted to name the Nine-banded armadillo and the Texas longhorn as the official State Small and Large Mammal, respectively. This Texas-born writer became personally acquainted with a taxidermized armadillo that made the rounds at a yearly White Elephant Christmas party. The Nine-banded armadillo’s cultural popularity continues to spread along with its geographic distribution. Due to several reasons, among them the reduction of most of their natural predators (coyotes, bobcats, mountain lions, wolves), armadillos are now found as far north as Kansas and southeastward to Georgia and most of Florida.

Is the armadillo dangerous?

Photo Credit: Peter Joseph

In 2019, a Texas Monthly article cited the nine-banded armadillo as one of Texas’s Top 12 most dangerous critters. This is because armadillos are one of the only mammals other than humans capable of contracting leprosy (Hansen’s disease). However, cases of humans contracting leprosy from ‘dillos are quite rare. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “the risk of contracting leprosy is very low, and most people who come into contact with armadillos are unlikely to get Hansen’s disease.” Nevertheless, Hansen’s disease experts say it is always the best practice to refrain from handling armadillos or consuming their meat.

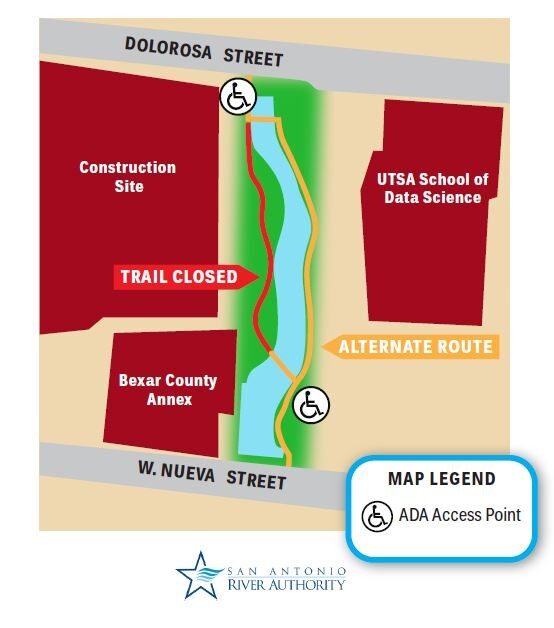

Where are Nine-banded armadillos found in the San Antonio River Basin?

According to citizen science sightings on iNaturalist, nine-banded armadillos have been spotted over 300 times in Bexar, Karnes, Wilson, and Goliad counties. It’s no wonder, as the San Antonio River Basin is home to over 8.800 miles of streams, and armadillos are usually found close to water sources. The moist, porous soil is full of invertebrates and easy for hungry armadillos to excavate! So if your property backs up to a creek, river, or riparian area, you’re more likely to encounter these armored animals.

A map of nine-banded armadillo observations in the United States from iNaturalist.org.

You might be surprised to learn that armadillos are also adept swimmers. If an armadillo encounters a small stream, it can hold its breath for up to six minutes and walk underwater along the bottom of the stream bed. In a larger body of water, like the San Antonio River, the armadillo will swallow air to inflate its stomach to twice the average size and swim across the top! So don’t be alarm-adillo-ed if you encounter one of these critters on your next kayaking trip!

How to Help nine-Banded Armadillos

Nine-banded armadillos play an integral role in the watershed ecosystems of our river basin. Not only are they a vital part of the food web, but they help humans by keeping lawn-harming grubs and other insects in check. If you have fruit-producing trees or shrubs in your yard, armadillos might see it as an open feast. This digging can sometimes cause damage to our yards and even the structural foundations of buildings, leading some folks to consider them pests. However, armadillos and humans CAN live in harmony!

Nine-banded armadillos can roll up into balls, right? Not quite. Only two species of three-banded armadillos can perform this trick. Photo Credit: Peter Joseph

Here are some ways to protect your yard while helping the ‘dillos!

- Block access to food sources. Install fencing around your vegetable garden and flower beds, or use wire mesh covers.

- Think like a ‘dillo and dig deep! If removing the armadillos’ food sources isn’t enough, installing an in-ground fence at least 18 inches deep with a 40-degree outward slant will help deter them from burrowing.

- Stay Safe. Call local wildlife control for guidance if you need to remove an armadillo or dispose of an armadillo carcass found on your property. If you MUST handle an armadillo, use gloves or a towel.

- Leave baby armadillos alone! Armadillos can start foraging alone at less than two months old. The chances are that its mother is nearby.

Next time you encounter an armadillo, give thanks for its contribution to our riverine ecosystems. By supporting these animals, we are supporting the health and well-being of our watershed.