Last Updated on January 30, 2024

In this edition of South Texas Natives, we’ll explore a beautiful bird of prey that you might want to give a hoot about! You’ll often hear a Barred Owl (Strix varia) before you see it! Also called the “hoot owl” or “eight-hooter owl,” Barred Owls have a distinctive call of 8–9 notes, described by birders as sounding like “Who cooks for you? Who cooks for you all?” These owls are sizable and stocky, just a tad bit larger than a Mallard Duck, with a rounded head, no ear tufts, and brown eyes. Barred Owls get their name from the contrasting color patterns on their chest and belly, which look like dusky, brown-colored horizontal and vertical bars.

Amazing Adaptations

Nature has equipped owls with some fascinating adaptations: strong talons, a razor-sharp hooked beak, excellent night vision, high-frequency hearing, noiseless feathers, and an ability to rotate their entire heads almost 270 degrees. These adaptations serve one primary purpose: catching various prey, including squirrels, mice, rabbits, amphibians, reptiles, fish, and other birds. How do we know what owls, including Barred Owls, eat? Many of us can likely remember our middle school science classes where we dissected owl pellets, the nuggets full of bones, teeth, and fur from an owl’s regurgitated meal. These pellets give scientists and your cousin Trevor in 7th grade an accurate insight into the dining habits of our local feathered mousetraps.

Compared to the sleek flight feather of the American White Pelican (Pelecanus erythrorhynchos) pictured on the top, an owl’s feather is velvety in texture and has a serrated edge that helps them fly silently. Photo Credit: Erin Magerl, Mitchell Lake Audubon Center

When hunting, a Barred Owl sits on an elevated perch, listening for prey and using its disk-shaped face like a radar to channel sound towards its ears, which are positioned asymmetrically on either side of its head. This positioning allows the owl to pinpoint the exact location of a mouse squeak or frog croak in multiple dimensions. Did you know that owls don’t have eyeballs? It’s true. Instead, they have sizeable rod-shaped eye tubes fixed in place, giving them a nocturnal visual sensitivity far greater than that of humans. Hence, the owl’s adaptation of double the number of neck vertebrae, 14 to a human’s 7, and a unique vascular system that keeps blood flowing to their brain as they swivel their heads.

Barred owls form mating pairs that stay together for life! #realtionshipgoals

Where and when can I see a Barred Owl?

Barred Owls are non-migratory year-round residents of Texas that thrive in mature old-growth forests with large trees and access to rivers, streams, or swamps. Large trees provide the owls with cavities high off the ground to make their nests, which they adorn with lichen, twigs, or feathers. They sometimes use nests built by other animals (like squirrels) and birds, including fellow native South Texas species, the Red-shouldered Hawk (Buteo lineatus). In fact, birders have observed Barred Owls trading off nests with the hawks, using them in alternating years or even one after another in the same season!

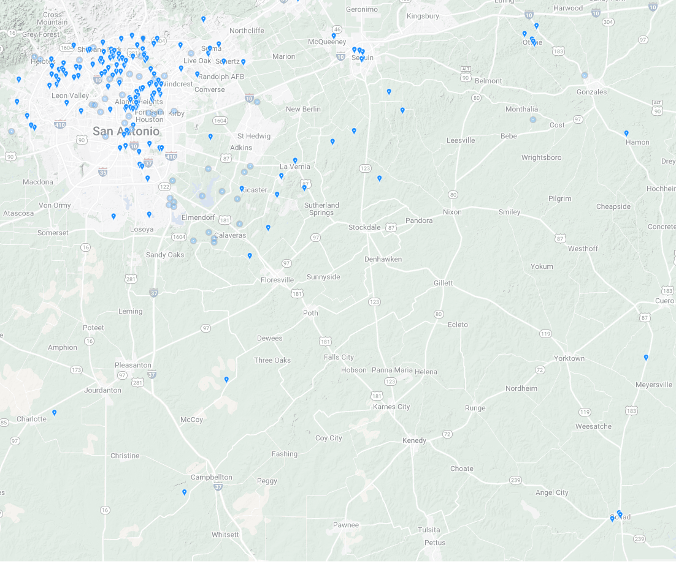

According to the iNaturalist app, there have been over 350 sightings of Barred Owls in the San Antonio River Basin, mainly in forested areas with large trees or along waterways.

A map of Barred Owl sightings in the San Antonio River Basin. Source: inaturalist.org. For a map of the Barred Owl’s range in North America, click here.

According to the Cornell Lab’s All About Birds, Barred Owls are easiest to spot near forested waterways at dusk, nighttime, or dawn, when they are actively hunting for prey. This aligns with my personal experience. I’ve seen (and heard) Barred Owls along the San Antonio River at Acequia Park and on the Salado Creek Greenway in Southeast San Antonio. I even observed a mating pair of Barred Owls nesting near my former apartment in Mahncke Park. Each evening near dusk, I would hear their loud hoots echo across our backyard. To increase your odds of spotting the Barred Owl, you can imitate the call with your voice and wait for one to swoop in and investigate you!

The Barred Owl’s main predator is the aggressive Great-Horned Owl, which eats eggs, young birds, and even adult owls. Pictured here is a juvenile Great Horned Owl. Photo Credit: Drake White

Is the Barred owl a threatened species?

Barred Owls are relatively numerous, and scientists have documented their populations as increasing since 1966 due to the expansion of their range with fire suppression in the West and tree planting in the Great Plains. Even so, urbanization, loss of habitat, and the side effects of climate change, like increases in spring heat waves and wildfires, threaten Barred Owls and many other species of birds in Texas. Displaced owls may flock to suburban habitats where they can suffer from a shortage of nesting sites and vehicle collisions. Human interference in a Barred Owl’s nesting area may even cause the parent to flee.

Want to be a Friend to the Barred Owl?

You don’t have to do it owl on your own! Here’s how you can join others in helping these remarkable raptors:

- Turn your yard into owl-friendly habitat! Leave dead and downed trees on your property (if possible) or build/install a nesting box. Find plans for building a nest box on the All About Birdhouses site.

- Avoid the “Cides.” Owls are at the top of the food chain, which means they can accumulate toxins from pesticides and insecticides that their prey has consumed. Instead, opt for natural pesticides and traps when controlling insects and rodents.

- Control Your Pets. Dogs, and especially cats, can maim and kill owls and their young during the breeding season. If you let your cats outside, put bells on their collar to help give birds a heads up!

- Give a Hoot! Learn More about owls by reading the suggested articles below, engaging in responsible birdwatching, and attending Mitchell Lake Audubon Center’s Owl Prowl in January.

With these actions, we can support owls of all stripes (or bars) and the health of ecosystems throughout our watershed!

An adult Barred Owl. Photo Credit: Peter Joseph (CC BY-NC-ND)