Last Updated on January 30, 2024

In our last stormwater blog series issue, we touched on a few tests River Authority scientists run on stormwater samples brought into our laboratory. If you remember from our first installment of the series, stormwater runoff is rainfall that gathers pollutants from our roads, sidewalks, and roofs and transports them into our local waterways. In Part 3, we will wrap up the remainder of these tests: nitrogen, heavy metals, and solids. Join us for the last leg of our journey and share your takeaways with others to help spread the word!

Testing for Nitrogen

Last time we reviewed nutrients, their impact and the analyses used to quantify them. Continuing this journey, we specifically want to cover nitrogen. Nitrogen comes in several forms, including ammonia (NH3), nitrate (NO3) and nitrite (NO2). We can find these inorganic forms in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems as part of the nitrogen cycle. Typically, ammonia is introduced through the atmosphere, through the breakdown of organic matter, and waste from fish and other animals. Then, tiny microorganisms convert this ammonia to nitrite and later into nitrate through a process called nitrification. These nutrients fuel plant and algal growth, which sustains aquatic communities, and the cycle repeats.

Microorganisms that drive the Nitrogen Cycle (shown here) convert Nitrogen into different forms that stimulate plant and algal growth. Thanks, bacteria! (Source: Nitrogen Cycle in Aquarium: Practical step-by-step guide to nitrogen cycle, Author: Arian Bobby)

But this cycle can experience overload when large amounts of these compounds are swept up and carried down storm drains into the river during a rain event, causing significant water quality issues. Like phosphorus and Total Kjeldahl nitrogen (TKN), which we discussed in the previous blog, excess nitrogen levels can cause algal blooms, low dissolved oxygen (hypoxia), and even become toxic to animals at higher concentrations. Eventually, these conditions can alter the entire ecological structure of a water body.

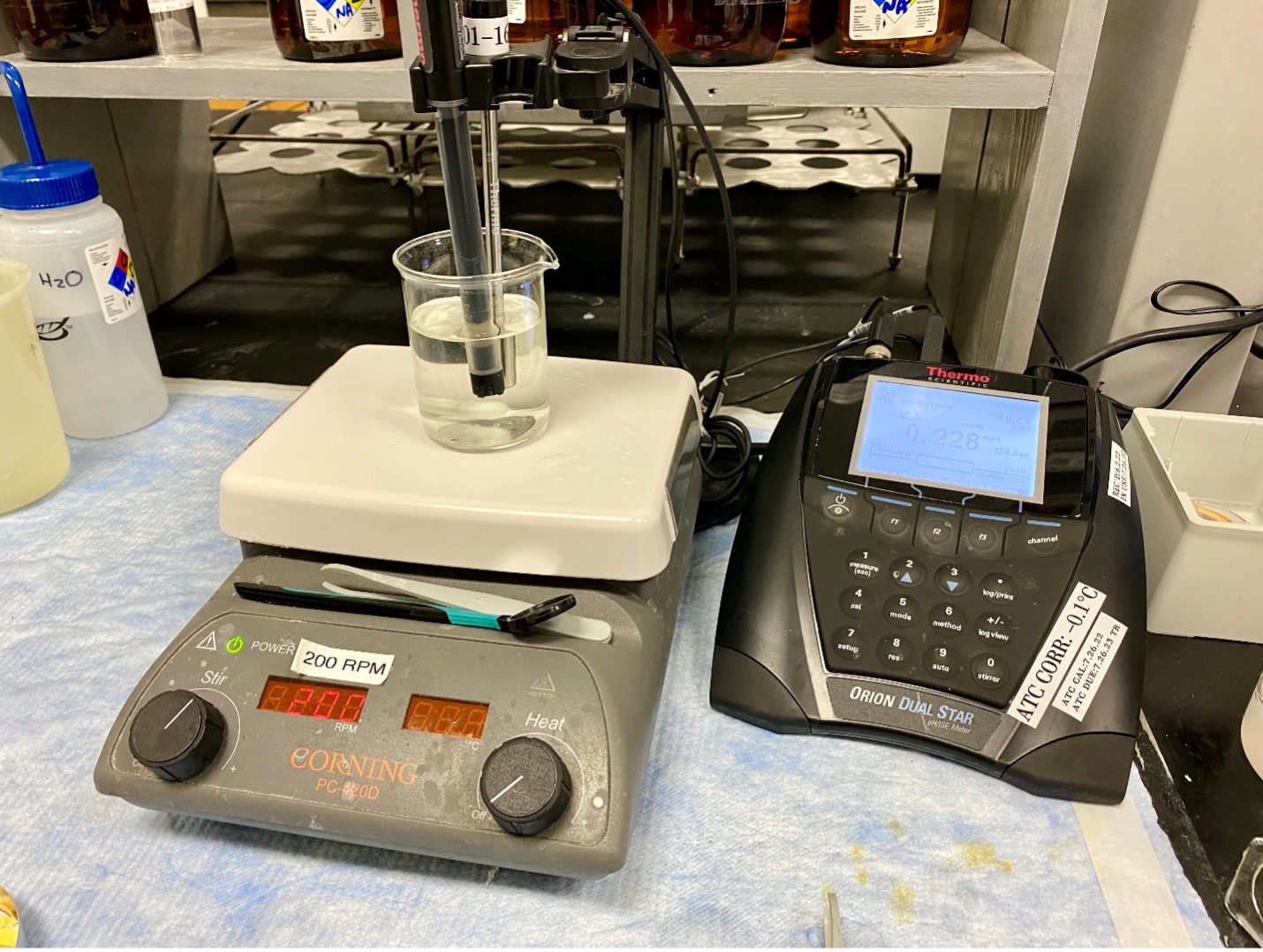

Testing for ammonia is simple! We use a probe that detects the concentration of ammonia present in a sample.

Water Quality Scientists determine the concentration of ammonia in water samples by using an ammonia meter.

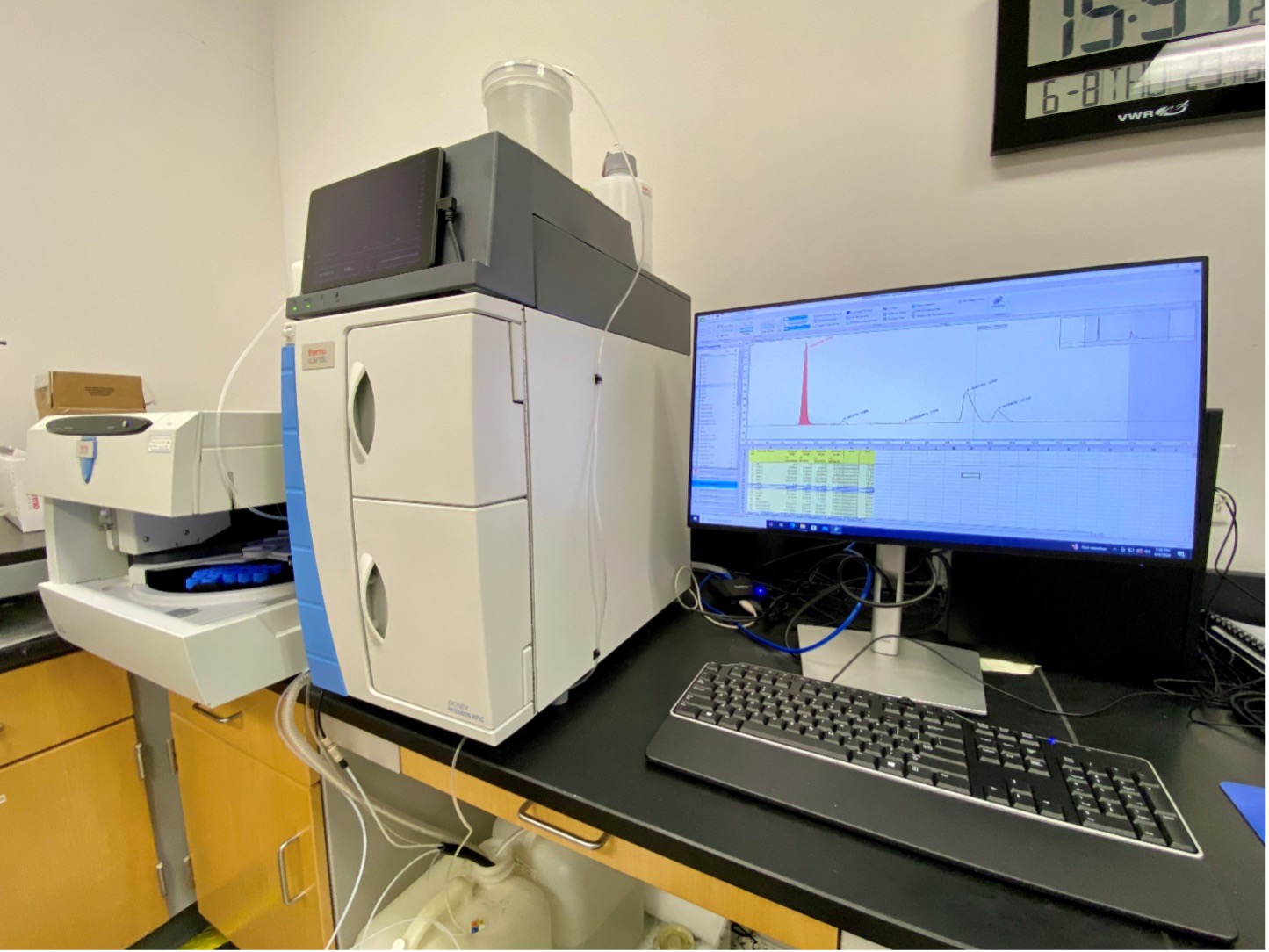

On the other hand, testing for nitrate and nitrite involves using a more sophisticated instrument called an ion chromatograph (IC). These anions are identified by first injecting a water sample into the device. The sample is fed through a special column separating the ions, and then a conductivity meter observes the order they exit. The time it takes for the ion to leave the column, called retention time, helps identify what we’re looking at.

Water samples are run through this ion chromatograph to determine the concentrations of anions like Nitrate and Nitrite.

Testing for Heavy Metals

Many heavy metals lurking around the city can also find their way into the river. No, we’re not talking about metal rock bands like Metallica. At the River Authority, we analyze samples for 24 different heavy metals, including arsenic and lead. Primary sources of these metals in urban stormwater are commercial industries and automobiles. It is essential to know how much metals are in the environment because, over time, they can build up in fishes’ bodies and be passed on to people and other animals when they eat them.

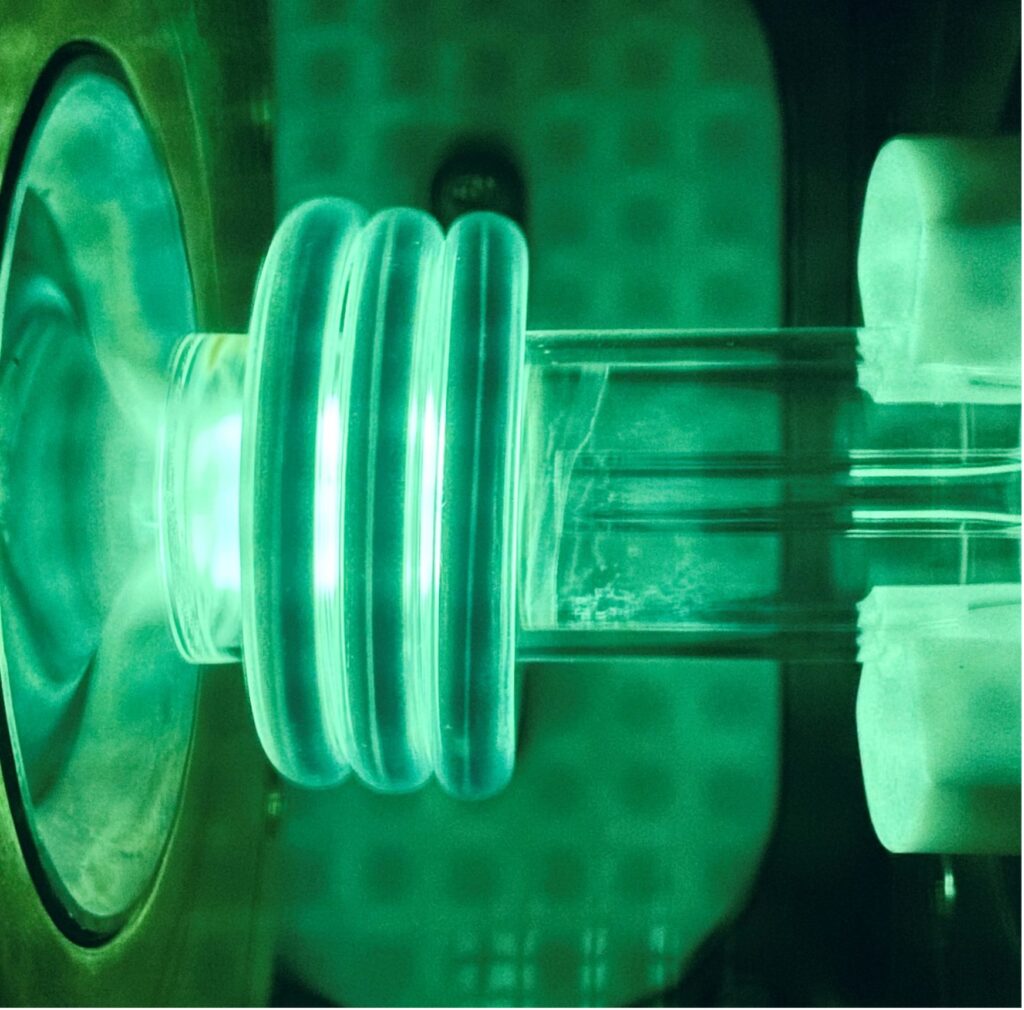

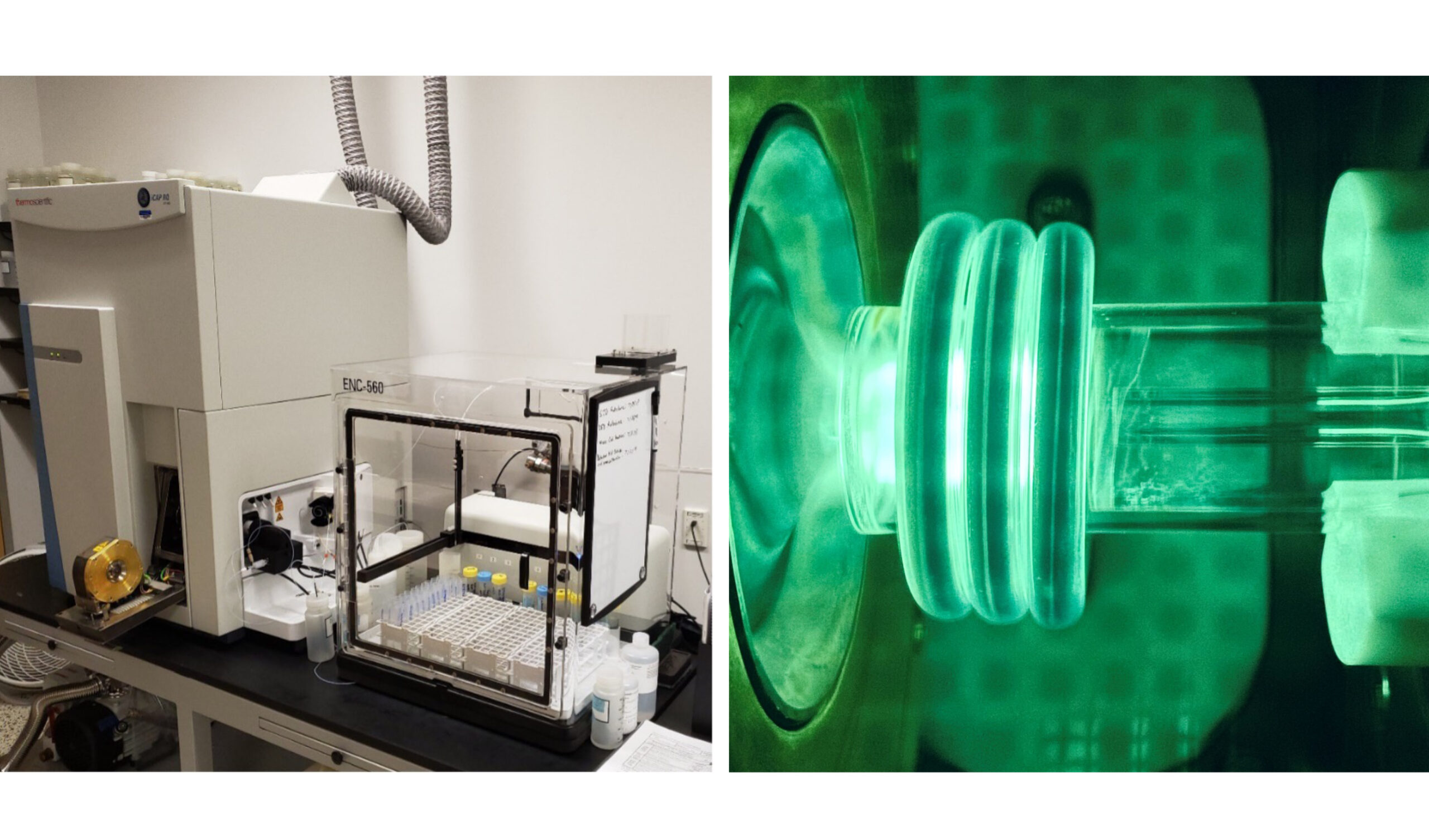

Samples must first be broken down using a process called digestion. Once digested, samples are sprayed into a chamber, creating a mist cloud. Then, using an Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer (ICP-MS), a plasma-torch laser breaks down molecules into separate elements and then computer software identifies them based on their mass. Knowing what metals are present can help us determine if fish in the area are deemed safe for human consumption. For help finding which areas are safe for fish consumption or aquatic life use, visit the San Antonio River Watershed Water Quality Viewer.

When they’re not rocking out, this Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer (ICP-MS, left) and plasma torch laser (right) are used to identify heavy metals in water samples.

Testing for Solids

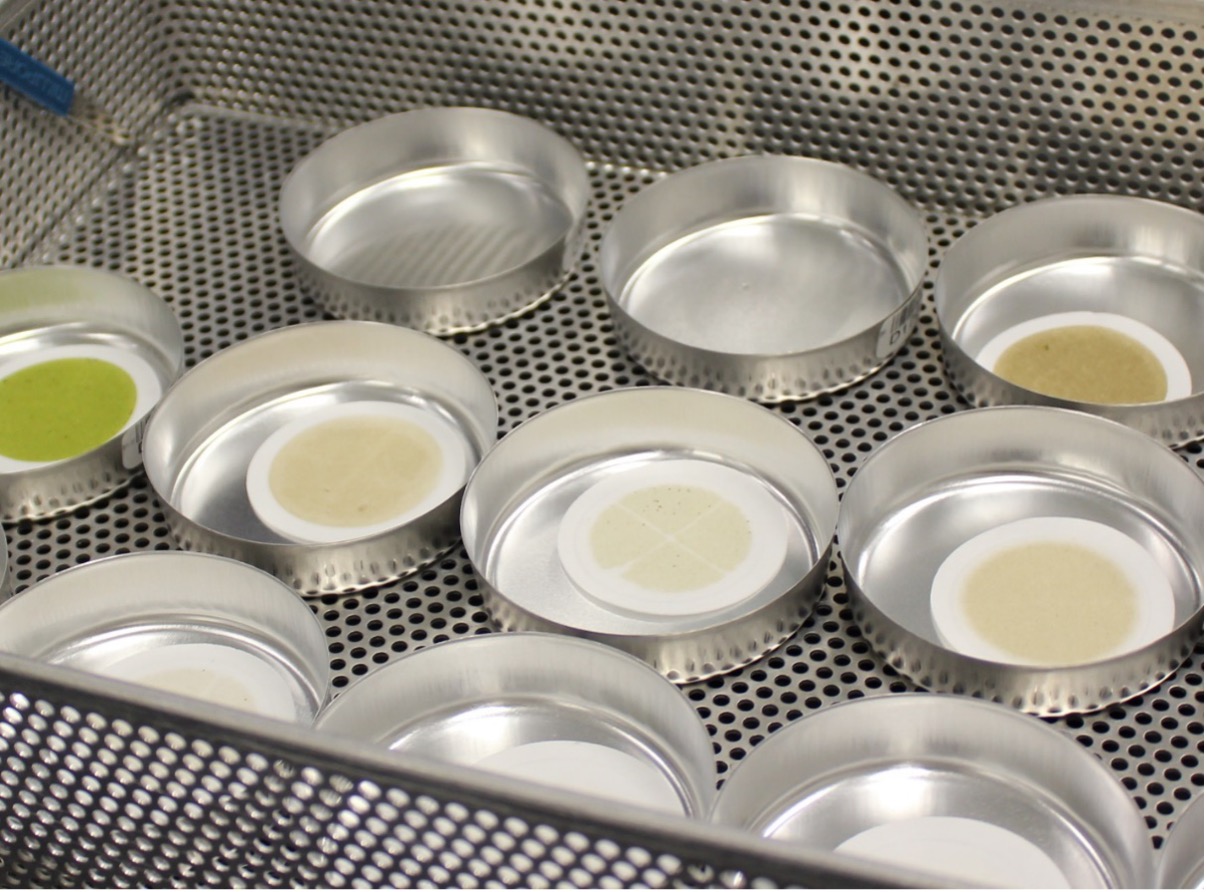

Solids are ubiquitous contaminants associated with stormwater runoff. Particles of dust, litter, and eroded sediment are often found on city streets and other impervious surfaces. They can pose many water quality, habitat, and aesthetic problems. High amounts of solids can increase water’s murkiness, also known as turbidity. Solids can also contribute to sediment buildup in waterbeds, affect desired plant growth, and damage habitats for aquatic organisms. Total Suspended Solids (TSS) is a method used to measure the amount of these solids. A water sample is vacuum filtered through a pre-weighed filter, dried in an oven, and weighed again. The weight difference determines the solids concentration. Based on these results, we can identify where any trouble spots may be located.

Particles of dust, litter, and sediment are filtered out of a water sample and dried on these TSS filters to determine the concentration of solids, allowing scientists to identify areas of local waterways where high turbidity may pose a problem.

What You Can Do to Keep the River Clean

Now that you’ve gathered some good insight into what our scientists learn from stormwater monitoring, you can better use the tools provided by the River Authority website to stay up to date on current conditions. Remember, you can keep our water bodies clean by preventing pollutants like excess fertilizer, automotive fluids, and loose sediment from entering storm drains and, ultimately, our creeks, rivers, and oceans. Please share what you’ve learned with others so they can contribute too!

Here are some additional resources if you want to learn more:

https://www.epa.gov/national-aquatic-resource-surveys/indicators-nitrogen

https://extension.usu.edu/waterquality/files-ou/Publications/Understand_your_watershed_Nitrogen.pdf